Avalanches

Snowmobilers top the list of those who die in avalanches across North America. If you plan to snowmobile in avalanche country, it is important to understand the potential dangers as well as the basics of avalanche safety. It is strongly recommended that snowmobilers take an avalanche training course to learn the avalanche danger signs they need to watch for when riding.

Click the curriculum tab to begin this course section.

Avalanches

Avalanches that involve people are not random. Rather over 90 percent of the time the victims or someone in their group triggers the snow slide. This means these avalanches could generally be avoided if snowmobilers learn to follow basic avalanche safety procedures. The following information provides a general introduction to avalanche safety.Five key safety guidelines for riding in avalanche country:

- GET THE GEAR: Ensure everyone has an avalanche transceiver, shovel, and probe on their person and knows how to use them

- GET THE TRAINING: Take an avalanche course

- GET THE FORECAST: Make a riding plan based on the current avalanche and weather forecast

- GET THE PICTURE: If you see recent avalanche activity unstable snow exists. Riding on or underneath slopes is dangerous

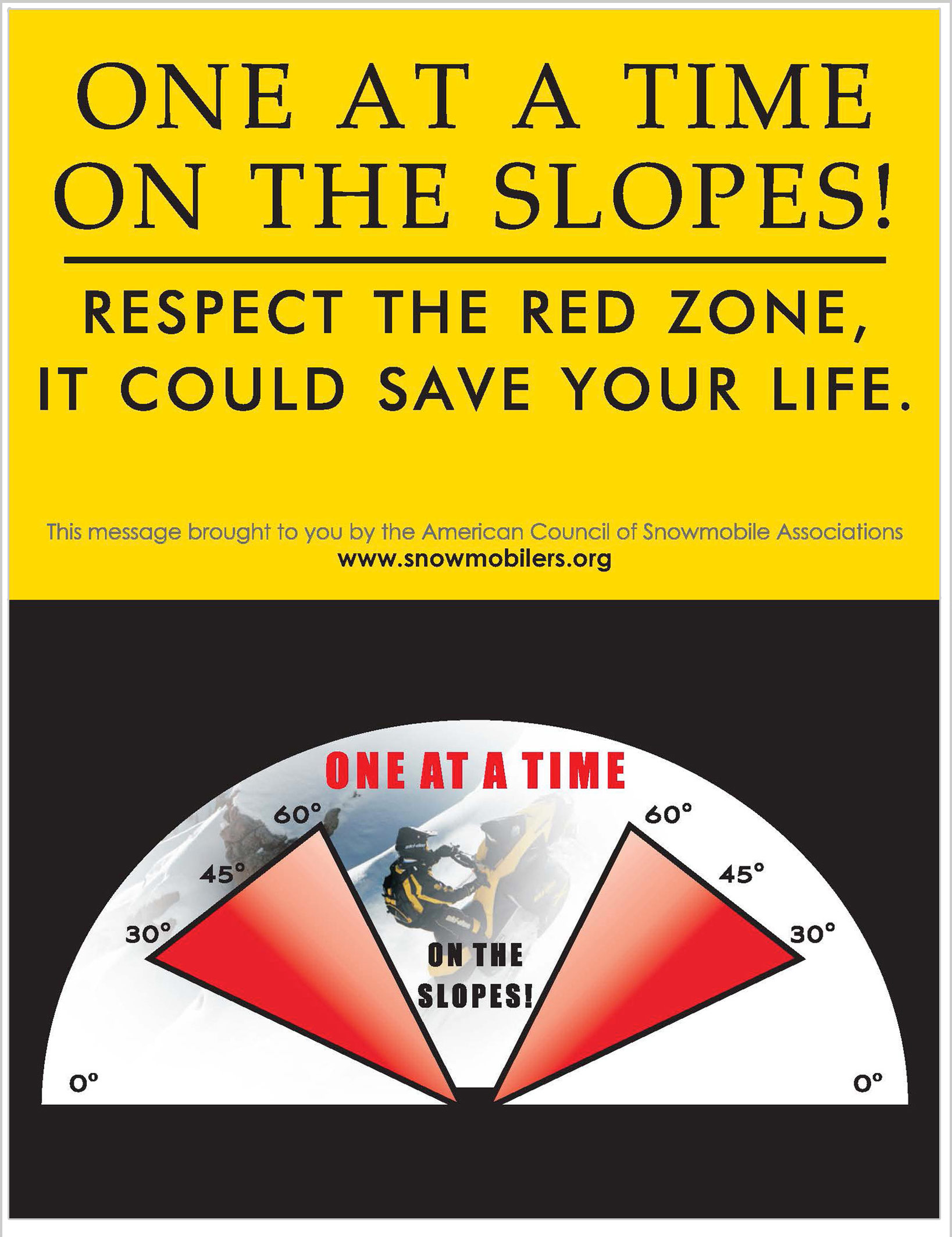

- GET OUT OF HARM'S WAY: One at a time on all avalanche slopes. Don't go to help your stuck friend. Don’t group up in runout zones

Many regions of the U.S. and Canada have avalanche forecast centers that issue daily avalanche forecasts during the snow season. Always Get the forecast for the area nearest where you plan to ride that day.

AVALANCHE.ORG Operated by the American Avalanche Association and the U.S. Forest Service National Avalanche Center

Avalanche Canada

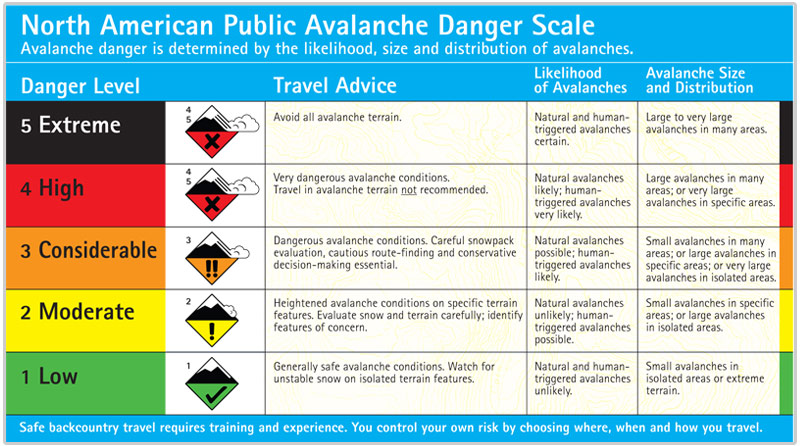

Daily avalanche forecasts are an important resource to help you make good decisions when riding in avalanche country. Find the avalanche forecast center nearest your riding area and make a practice of checking daily forecasts, which will rate the avalanche danger scale as follows:

Three key travel procedures for riding in avalanche country:

Following these three basic travel procedures could help cut the number of avalanche fatalities in half:

- Ride up or down onto, or across, steep slopes only one snowmobile at a time; the rest of the group should watch from a safe location until the rider on the slope safely clears it before the next person proceeds

- Do not park at the bottom of a steep slope in single file; instead park to the sides of the slope with your snowmobiles side by side and pointed away from the slope

- Never go up on a steep slope to help someone who has become stuck, since adding your sled to the slope could trigger an avalanche

High Marking Safety

'High marking' is the practice of climbing steep slopes with a snowmobile to attain the highest mark/location on the slope or to get 'over the top.' It's one of the most dangerous things you can do on a snowmobile and accounts for over 60 percent of avalanche fatalities involving snowmobilers.

Any slope steeper than 25 degrees can potentially slide, although prime slopes for avalanche conditions are generally 30 to 45 degrees up to a maximum of 60 degrees (slopes above 60 degrees are generally too steep to hold snow cover). These are the exact same slopes snowmobilers love to ride and high mark on. Understand that riders do not have to be up on a steep slope to cause an avalanche; they just have to be in the vicinity and connected to the slope to trigger a slide.

If you are going to high mark, adopt the following safe riding habits:

- Stay alert for clues of instability, even while driving to the trailhead. Ride your sled onto small cut banks and slopes to test snow stability. Periodically stop your machine, remove your helmet, walk around to get a feel for the snow, and visually scan the area

- If the snow is unstable, you should notice one or more of the following clues:

- Recent avalanches (don't play on similar, unreleased slopes)

- New snow (the added weight can overburden buried, weak layers)

- Wind loading (wind can deposit snow ten times faster than snow falling from the sky—as a result weak layers can quickly become overloaded)

- Rain (weakens snow quickly, but causes the top layer to stabilize when refrozen)

- "Whoomphing noises" (indicates the collapse of a buried weak layer)

- Shooting cracks in the snow surface that run across the slope (indicates the snow is ripe for fracturing and is beginning to slide downward)

- Hollow-sounding snow (indicates a buried weak layer of snow)

- Signs of rapid or intense warming (the snow will weaken quickly and create unstable conditions — often see small 'pinwheels' or snowballs that have rolled down the slope)

- Choose slopes that have been stripped by the wind (windward) versus slopes that have been loaded by the wind (leeward). Snow that is rock hard can still avalanche if it is poorly bonded to the layers of snow below it, so be wary of steep, smooth, leeward slopes

- Start out on the less steep slope angles and on the side of a slope instead of center-punching it. Do your first runs low and fast rather than maximizing your commitment and exposure by climbing as high as possible right away. If possible, do your first runs from the top down to get a feel for the snow and to improve your chances for escape. Try to turn toward the edge of the slope rather than turning toward the middle

- If unsure of the snow stability, favor slopes that have recently avalanched over those that have not yet slid. You can still ride on unstable days — just choose slopes less than 25 degrees that are not connected to steeper slopes

- Unless you know the snow is stable, do not approach steep convex rollovers or aim for a large rock or tree isolated in the middle of a steep slope. These are places where the snowpack is under greater stress, and as a result you are more likely to trigger a slide. Also, be suspicious of steep areas where the snow is shallow and weaker

- Avoid deadly "terrain traps" such as gullies, steep-sided creek bottoms, or slopes that end in depressions because they pose a high probability for deep burial. Do not ride on slopes with cliffs below. Favor slopes that are fan-shaped at the bottom and do not have obstacles likes rocks or trees to crash into. Concave bowls are nasty traps because the fracture propagates around the slope and all the debris collects at the bottom. This is why it is not uncommon for snowmobilers to become buried under 10 to 30 feet of avalanche debris

- Always allow only one rider at a time up on the slope. If that person gets stuck, do not send a second rider to help since it is all too common for the second rider to turn above the stuck snowmobile, triggering an avalanche onto the stuck rider who becomes a sitting duck below

- Everyone else in the group should be watching the one climber from a safe spot, off to the side and parked well away from the bottom of the steep slope. Do not count on being able to outrun a slide if you're parked directly at the bottom of a steep slope. Get in the habit of parking parallel rather than one behind the other. Also have all parked snowmobiles pointed away from the potential avalanche slope and ready to start

When riding off-trail in known avalanche terrain, try to limit your group size to only three or four people. It can be less safe when the group size is larger since it becomes more difficult to communicate good choices and follow safe travel procedures. However do not split your group if it is larger; rather pay extra attention to safe travel by stopping more often to periodically look for clues of instability in the snowpack and to discuss potential avalanche hazards with the group. If there is any question about being able to ride safely, be smart and choose another area or day to ride.

NEVER travel above your partner. Remember, one at a time on steep slopes, and park in safe spots while watching the person who is exposed to the avalanche hazard while on the slope.

Each rider in the group should wear a transmitting avalanche beacon and also carry a probe and shovel in a pack they wear. If the tools you need to save your friend are on your buried sled, your friend may die, so always carry your rescue gear on your person versus on your snowmobile. Before you drive to the trailhead, confirm that all members of your group have their rescue gear and knows how to use it. Check to ensure all beacons work in 'transmit' and 'receive' modes.

Always ride with your helmet securely fastened since many avalanche victims actually die from blunt-force trauma. Full-face helmets have saved avalanche victims by providing some built-in air space; although you can't count on this, it does potentially provide an extra measure of safety.

Assumptions can kill you when snowmobiling in avalanche country. Instead, you must continually make reasoned observations and decisions to help stay safe. Avalanches don't care what you want to do or how skilled you think you are, so don't make the mistake of becoming at ease simply because you've ridden an area before. It does not matter that it is a nice day, since most avalanche accidents actually happen on blue-sky days after storms. Don't assume it is safe just because there are tracks on the slope. And you're not safe and invincible just because you're wearing a beacon.

If your group needs to actually use their beacons it means someone messed up, big time. While beacons may help save an avalanche victim if the rider is lucky and found within 15 minutes, beacons are 'false security' and may just as likely be used to recover a body. You're in avalanche country, so keep the brain engaged and continually think about your next move versus falsely assuming you'll always have a safe day.

Cornice Safety

Cornices are the overhanging deposits of wind-drifted snow that form along the leeward side of ridge crests and gullies. Cornice breaks can be caused by additional new snow, wind loading, warming, or the weight of a person or sled on the cornice.

If you like to 'catch big air' by jumping cornices, know that even if you don't break the cornice, the snowmobile's landing shock-loads the slope (like a detonating bomb) and can trigger an avalanche. Do not approach cornices from the bottom or ride on slopes that are overhung by cornices above them. Always be extremely careful of cornices since they often break farther back than you'd expect and when they come down they bring a huge amount of hardened snow with them.

When approaching any ridge, slow down, think cornice, and make sure you're riding, parking, or standing on snow that has solid ground beneath it. The best practice is to stay a long distance back from the edge. Realize you can be fooled by bushes or small trees that sometimes extend through a cornice from the slope below — meaning the underside of the cornice extends much further back beneath than you realize.

Avalanche Rescue

Your smartest option is to practice good safety habits to avoid ever getting caught in an avalanche. However if an avalanche does occur, there is generally only a 15 minute window to rescue a buried victim before they die from asphyxia. There is not enough time to go for help, so you and the other riders in your group have to become the rescuers. About 65 percent of riders buried in an avalanche survive when their partners are able to perform a rescue, while buried riders die about 80 percent of the time whenever their partners leave the scene to go for help. You simply have to stay at the scene and search for your buried partner.

Many snowmobilers continue to venture into the backcountry untrained and unequipped to rescue someone buried by an avalanche. Tools for an avalanche rescue include: brain, beacon, probe, and shovel. You must carry the last three and engage the brain in order to have a successful rescue; otherwise the exercise becomes only a body recovery.

Always carry rescue gear when riding in avalanche country and also make sure your riding partners are equipped with rescue tools. While some riders have objected to buying an avalanche beacon, probe, and shovel saying it is 'too expensive,' it's certainly not when compared to you, a friend, or family member becoming severely injured or dying in an avalanche.

If you're completely buried, a beacon may be the only way you can be located and dug out within the 15-minute window for survival. Avalanche debris quickly sets up as hard as concrete and there are unfortunately too many stories about people trying to dig a victim out with their hands, helmet, face shield, or windshield. That simply does not work because the snow is too hard. You must carry a real shovel (preferably aluminum or steel versus plastic) on you in a pack. A probe is also important to help pinpoint the buried person and to minimize digging time; it is essential if you're looking for someone who failed to wear a beacon since it allows you to quickly spot-probe around the debris field.

Most importantly, train for the use of rescue gear. Practice with it regularly to ensure you know what to do, and can act quickly and instinctively in the event one of your partners becomes buried in an avalanche.

If Caught In An Avalanche:

- Try to stay on your machine and ride out toward the side

- Keep your pack on since it helps give you some flotation

- If knocked off your sled, push away from it to reduce your chances of being injured and FIGHT HARD to stay on top of the moving snow by "swimming"

- Attempt to roll onto your back; you have a better chance of survival if buried face up

- As the avalanche slows, thrust your hand straight up, expand your chest and use your arm to create airspace

- Try to remain calm, so you will use oxygen at a slower rate

If You Are A Rescuer:

- Watch the victim! Establish the last place you saw the victim and mark it

- If you did not observe the slide, question any witnesses about the number of victims, the location they were last seen, and whether or not the victims were wearing beacons

- Make sure it is safe to search—the slope that has just avalanched is unlikely to slide again unless it has reloaded or has adjoining paths funneling into the same area that have not yet released

- Conduct a thorough initial search of the debris below the area the victims were last seen. Look carefully for clues (e.g., sled, boot, glove, blood), probe around clues and in likely catchment areas such as flat benches or dips in the terrain, next to rocks or tree-wells, and at the toe of the debris

- Leave clues (including sleds) in place; they may help establish the victim's line of travel. Most buried snowmobilers are found no more than 200 feet from their sleds, in roughly the same fall line. More often than not, the victims are upslope and within 40 feet of their machines

- If wearing avalanche beacons, conduct a beacon search (which you should have practiced many times before!) simultaneously with the initial search

- If the victim is not located by any of these search methods, systematically probe the most likely search area

- When you locate the victim, dig fast but carefully. Free the victim's mouth and chest of snow first. Then have first aid gear ready for treatment and be alert for airway problems, hypothermia, and blunt-force injuries